The Beast

By Isabella Elliot

When I first got my doctorate, I started doing research at an observatory in the middle of a desert. There was nothing for miles in every direction, just flatland and baked brush. Day faded into night in a blue to yellow to pink gradient, then starlight would illuminate the observatory grounds and everything would stand still for hours on end. Roads evaded the property in a curving snake of blacktop out by the interstate. The only way to get there was on a dirt road traveled exclusively by the observatory’s small team of transportation Jeeps. There were no towns or cities, just me and the other astronomers and researchers that occupied the facility. It was brand new, equipped with all the best gear our grants could buy. The telescopes they were making those days were more powerful than they had ever been before. We could see hundreds of light-years out of our own galaxy with perfect clarity. We could even automatically log, interpret, and view images of gas movement and radiation, instantaneously layered over the actual view from the telescope. Humanity glimpsed at black holes, nebulas, celestial bodies, and everything else that evoked feelings of both jaw-dropping awe and existential dread.

By the time I was in my early thirties, I thought I had seen everything. I’d been staring at stars and planets since I was an undergrad in the early 2050s, and redundancy had taken hold on me. It was during one of my routine checks of Saturn that I noticed the anomaly. I focused the telescope on Saturn’s coordinates, ready to log its new position in a never-ending loop, but all I came across was empty space. At first I thought that my telescope was off, so I adjusted the settings and looked again. Still black space. I checked the coordinates on my dashboard. They were correct. I zoomed out to make sure the surrounding stars were in the same positions, but instead of stars I stared into the gaping maw of a black hole. The space around it was distorted, all elongated balls of light swirling into an abyss of empty space. Jupiter was drifting into the void, its gas curled into the event horizon like coffee swirling down a drain. All the moons knocked into each other and fractured, then fell into the abyss and out of existence. Venus tumbled in right after, sucked into the darkness and devoured by the void. It was eating our solar system. Stunned, I dashed away from my station, running to get my colleagues.

“A black hole! There’s a black hole where Saturn should be!” I screamed as I ran down the aisles of busy scientists. Immediately a crowd formed around my telescope, all panicking scientists biting their nails and whispering anxiously to each other.

“Let me have a look,” the head astronomer demanded, moving his face to the eyepiece. He stared through the lens for a few moments, his brow furrowed in deep concentration. Then he turned to me, annoyance plastered across his face.

“That’s Saturn. You’re looking at Saturn.”

“But there was just nothing there!” I asserted.

Around us, the scientists rolled their eyes and dispersed, headed back to their normal work stations. I pressed my face to the telescope. I stared at Saturn; its characteristic ring and pale yellow color stared back.

“It was just there,” I said in disbelief.

The lead astronomer shook his head.

“Never play a joke like this again, Nick.”

Then he left me alone at my work station, numb and confused.

That was nearly sixty years ago. I’ve rebuilt my integrity since. A lifetime of research and hard work does that for you. It’s all a numbers game really. A destroyed social standing, 400 scientific papers, about ninety books and textbooks, and a Nobel Prize later, I’ve become a real scientist again.

The observatory has since shut down. All the other researchers left for bigger and better things, but I stayed here with Jonathan. I own the observatory now, and Jonathan lives here with me. It’s a blissful life of research, far from my former colleagues. They never got over the whole Saturn thing. Oh well, after decades of dealing with their judging glances and “Where’s Saturn, Nick? C’mon, tell me where it is” jokes, I’m happy to be rid of them. It’s just me, Jonathan, and the stars, and I couldn’t be happier.

Jonathan wakes me at the usual time. He chimes my alarm over his speakers, then the door slides open and he steps into the room holding my breakfast. I sit up and face him.

“Good morning, sir. I’ve brought your breakfast. The weather is ninety-six degrees Fahrenheit. You have no scheduled events today.”

Jonathan walks across the room and places the breakfast tray over my lap.

“Thank you, Jonathan.”

“My pleasure, sir.”

He stands near the window and stares out into the desert.

“Clear skies today, sir. Perfect for lunch away from home.”

“I’d like that, Jonathan.”

He turns to me and straightens up, staring off into space as he does calculations for today’s flight.

Jonathan’s an 0525 Model, built for maintenance and personal care. He has the same face and body as all his brothers in the 05 line: peaches and cream silicone skin with sapphire-studded eyes and dark brown faux hair, long and swept back. His skeletal structure is modeled after that of an athlete, broad shouldered and tall. He has the eternal physique of a twenty-something with AI that lives to please. There are only twenty-four other 05 models, and they were all gifted to other notable men and women of science as humanoid personal assistants. My research is a solitary job, and Jonathan helps keep me sane. In my case, Jonathan was modified to be vigilant to the needs of the elderly (a necessary addition, considering I’m almost ninety-three) and upkeep of scientific buildings and structures. He has been living here since the observatory shut down and became my private property, taking care of me and the building’s complex facilities with the precision and timeliness that only a top-of-the-line android can. His duties include cleaning the facility, monitoring the grounds, responding to my requests, and caring for my health. He has the technological and scientific knowledge of thousands of PhD holders and the physical strength to carry objects up to 2,000 pounds, all in a compact android.

He stands patiently and waits for me to finish my breakfast, hands clasped behind his back. Then he picks me up and places me in my wheelchair.

“I have cleaned the observation room, sir. The telescope is prepared for your daily logging when you are ready to begin. I will be tending to the Heart of God. If you have any need for me, please let me know.”

Then he leaves and the door slides shut behind him.

I set up the telescope so I can start logging when we get back from lunch. Then I go check on Jonathan as he warms up the Heart of God.

The HOG is a craft that Jonathan and I built together. It looks like a hybrid of an old bomber plane from the early 2000s and a space shuttle, sleek and aerodynamic but still spacious. It has an observation bay, a storage unit, a refrigerator, and a bathroom. Just perfect for a midday getaway.

My research has enabled me to do great things, including build the world’s first personal spacecraft. Everyone is still trying to figure out commercial spaceflight, but me and Jon-tron have it in the bag. Jonathan and I sometimes turn off the HOG’s radio signal and go to Earth’s orbit for lunch. My colleagues in observational studies know about my craft, and I wave mockingly at their stations while I eat my zero-gravity PB&J. They’ve asked about the tech, of course, and a lot of facilities have offered me billions for my design, but this is between me, Jonathan, and our midday meal.

“Departing in three . . . two . . . one . . . liftoff.”

The Heart of God takes off from the launchpad behind the observatory and travels toward the deep blue of the midday sky. Jonathan sits on the floor next to my wheelchair, a brown picnic basket in his lap. He hums absentmindedly, a small smile on his face.

We shoot straight upward until the sky in front of the HOG’s nose is black and star splattered. The ship’s gravity system engages immediately, holding us down in a perfect imitation of the conditions on Earth. I angle the craft so that it’s facing the glow of the planet beneath us. An expanse of green, blue, and brown unfolds before Jonathan and I, and I stare contentedly out the window while Jonathan unpacks our lunch. He hands me a sandwich, then stands by me and stares out at the rotating landscape.

“You can see our house from here,” Jonathan jokes as he points to a large patch of light-brown land.

“It’s not so much a house as it is an observatory, Jonathan.”

“I guess that’s true, sir.”

Aside from the addition of a launchpad to the grounds, the observatory hasn’t undergone any major changes. I simply made my living quarters one of the former rooms that used to house the astronomers when they were assigned here. It’s still a scientific building. The only difference is that there is only one scientist in it now.

We’re quiet for a while, staring out the window next to each other.

“Would you like to hear a fun fact I learned, sir?”

“Sure.”

“Earth is the only planet in our system not named after a Roman god or goddess.”

“Intriguing. What do you think that means?”

“I don’t know, sir. Sometimes I question why humans do the things they do. You’re very funny, naming your own planet after dirt.”

I chuckle. “Well then, what would you call it?”

Jonathan is silent for a second. He squints and stares down at what is now the dark side of Earth, illuminated by artificial lights from distant cities.

“It’s where we live, so I think I would call it Home.”

I smile at Jonathan, his silicone lips curve upward too, showing perfectly white porcelain teeth. The earth begins to glow again as we reach the side illuminated by the sun.

“We’ve completed an orbit, sir. It’s time to land.”

When we return to the observatory grounds, I go do my daily logging. Keeping track of the planets, constellations, and surrounding galaxies is a daily habit. It helps remind me that nothing will change up there except for the things that are meant to change, like the birth and death of stars and solar flares reaching out their arms to surrounding planets in wisps of orange light. I have to assure myself that everything is where it should be. I have to make sure Saturn is still there. It’s an anxious habit.

I begin the process, always checking Saturn first.

Saturn: coordinates constant, composition stable, no change, location logged.

Mars: coordinates constant, composition stable, no change, location logged.

Andromeda: coordinates constant, composition stable, no change, coordinates logged.

Virgo constellation: coordinates constant, composition stable, no . . . no . . . what’s that?

I’m staring at a blur of light that I’ve never seen before. It’s a speck of glowing space shining from just under Virgo’s lowest star, very faint but still visible. I check my log from the previous day. No notes of any changes in the relative vicinity of Virgo. This is new.

I zoom in on the light. It’s still too small; I zoom again. And again. It’s far away, becoming brighter. Zoom in . . . zoom in. . . stop.

I feel my mouth fall open in shock as my body stiffens. My hands shake on the controls as I try to comprehend what I’m seeing. I stare at it, and it stares back.

It’s a face. Two burning balls of white light and a stretched smile of sharp teeth, illuminated by some backlight that I can’t find the source of. It’s far, but massive. I take a photo of the image and call Jonathan in to clean the lens again, in case I’m viewing a smudge. He cleans it and I recheck the coordinates. Still there. In a jumble of panicked words, I tell Jonathan what I have seen.

“That is strange, sir,” he tells me. “May I see this anomaly?”

I move and allow Jonathan to look through the lens. “Yes, very odd.”

“Jonathan . . . what is that?”

Jonathan scans his databases for an explanation. He stares into space, searching all the servers he can access. “I don’t know, sir. The international databases have nothing of its nature. Maybe speaking to colleagues would be useful.”

I glance at the telescope once more.

“Whatever it is . . . it’s as big as Earth.”

I called the Bureau of course. Then everyone else in my field who would care. I expect some laughing and retelling of my infamous Saturn incident, or maybe even outright rage at wasting their time, but they all respond with sincerity and fear. They all have noticed the anomaly too, and are baffled by the sudden appearance of a smiling face staring at us from the far reaches of space. I hound them for more data. We all have the same coordinates and have captured images of two white eyes and a long, sharp-toothed grin, but beyond that, no one has anything of use. For now, we keep this information under wraps: governments and high-level scientists only.

Jonathan comes into my office during my flurry of phone calls.

“Sir, I think we should turn on the television. I have found a piece of information that might be of interest to you.”

I trust Jonathan’s judgment. He has processors capable of collecting and interpreting thousands of terabytes of information per second. If he thinks he knows something that might be useful to me, I will listen.

“Ok,” I say, dialing in another number.

As it’s ringing, Jonathan switches the television on to a news channel. The voice-over starts. “Renowned psychic and spiritual guide Marie Anderson, who has correctly predicted over one hundred cosmic events, claims that she has become blind from one of her visions just hours ago. While on a walk with followers in a local park, Marie suddenly gazed into the sky and began to scream as her followers watched in horror. She began to seemingly cry blood and clawed at her face, to which bystanders called paramedics. Let’s go to Marie’s hometown in Austin, Texas. Caden? Can you hear us, Caden?”

“Yes I can, Tom. I’m here with Marie. Marie, what was it you saw?”

I look up to the television. The reporter is holding a microphone out to a woman squatting in a patch of grass. She’s sobbing, with her hair sticking up at all sides, holding herself and quivering as a paramedic places a shock blanket around her shoulders. She turns to face the cameraman. Her eyes are pure white, the pupils missing, bloodshot through the center like a single-color jawbreaker. She’s clutching her middle as though she’s falling apart.

“A beast,” she says between sobs, “A giant beast in the sky!”

Reporters clamor around her, microphones coming into the frame from all directions.

“Marie!”

“Can you tell us what this vision might mean?”

“What was the beast doing?”

“It had glowing eyes and it could see straight through me . . . . The . . . the thing was smiling with so many teeth, thousands of sharp teeth, and it had a body and legs, and . . . and . . . and claws on its fingers. Its face became the sky and it looked into my eyes. It burned my face with its stare! It burned my eyes out! It’s going to eat us! It . . . it . . .”

Marie stops sobbing and shivering. She looks directly into the camera, her milky eyes staring straight through the lens. Her stare is unwavering and intense, and her eyes are red from sobbing, yet her face has stopped quivering. She takes in a steady breath and then speaks in a voice that’s barely a whisper.

“I’ve seen the face of death and it is smiling.”

News of the face spreads in a matter of hours. A few days later, the Bureau comes forward with a full statement. They publish a video of the chairman speaking to an audience of reporters and researchers. Composure runs thin, and some people in the press conference are crying, others are scientists who look like they haven't slept or eaten since they learned of the face. I am one of them, watching from my observatory with Jonathan at my side urging me to eat a meal he had prepared for me. I tell him I’m too busy.

“We don’t know what this thing is, but we do know three things. Firstly, it appeared just below the Virgo constellation, and we know the exact coordinates of its origin. Secondly, it is massive. It’s the size of our planet, possibly even larger.”

The chairman grips the sides of the podium and looks down. He licks his lips and inhales deeply.

“Lastly,” he says, “it’s coming closer.”

They’re right about all three things, especially the last one. I’ve been keeping tabs on its location and logging its position hourly since the first sighting, and it travels hundreds of light-years closer in a matter of minutes, each time jumping from one region of space to the next effortlessly. We still have no definite idea of its shape despite Marie Anderson’s description. All we have are those eyes, smile, and the unease of its looming presence. I set Jonathan to interpret the data and measurements I gave him regarding the face’s coordinates, asking him to search for an explanation. He keeps coming up with nothing.

It has been a week since the Bureau’s statement. The beast is now in our solar system. It is gripping onto the side of Neptune, still staring at us with a toothy grin. We finally have a full visual on it.

The face is a quadruped beast with three long tendrils coming from its massive paws, a talon positioned on the end of each one. Its flesh is milky white, full of gaping pores and dripping orifices. It has a frog-like head with an unnatural jaw and thousands of sharp teeth, constantly curved in a menacing grin. Its eyes are burning balls of white flame, sitting close together on the top of its head, front facing and ominous. I stare at the beast for hours. It stares back. It doesn’t move. Yet, it still comes closer.

Jonathan, being an android, is not nearly as distraught as I am about the beast, but since he is programmed solely for the observatory’s upkeep and for my well-being, he insists on helping ensure my safety. “Sir, please allow me to pack the craft with necessities in case the beast poses any direct threat to the condition of Earth. It’s in your best interest to escape, should the need be.”

I allow Jonathan to pack the ship, just in case. He’s been keeping a watchful eye on me lately, usually right by my side during my observations of the beast. I am thankful for his company.

The thing is submerged in Jupiter’s gas now. Earth is in total panic. Everyone wants to leave the planet immediately, but commercial rockets can only accommodate three to four passengers per trip, and those are far and few in number. My craft can hold only ten. Even if every functioning rocket is deployed, only about a hundred people can be saved. On a planet of nine billion, that’s about 0.000001 percent of the population. Havoc has broken out in every nation. Everything is broken or on fire, and from what I’ve seen on the news, there is no end in sight. It’s the end of the world scene from every apocalypse movie: shattered storefronts, looting, crime, and death. Anything goes during the end of the world. Lucky for Jonathan and I, the observatory is remote enough from the general population to not be affected by the chaos, but I still feel the panic and confusion. It’s thick in the air when I go outside, heavy with the knowledge that this planet may be facing its end very soon.

My colleagues have been calling me, asking me to bring them on my spacecraft and fly us far away from Earth. I agree to bring who I can fit.

It is time for us to leave. The beast is nearing our moon, and gravity is already shifting due to its massive presence. Jonathan wheels me into the Heart of God. We depart in an hour.

“Everything is packed, sir. You need only to operate the ship when all the occupants have arrived.”

He releases my chair.

“My mission is complete. Thank you for allowing me to serve you.” He makes a move toward the door.

“What mission have you completed, Jonathan?” I ask him.

“That of your personal care, sir.”

Jonathan’s programming must be facing a division of priorities. He thinks that I will be eternally safe in the craft. He thinks that my care is complete, and that he now only has the mission of maintaining the observatory.

“No, Jonathan, you’re coming with me.”

“Sir, I have no mission with you any longer. Once I leave this craft, you are safe. This craft is stable and has all the resources to sustain a human. There is no need for me to accompany you.”

“Jonathan, don’t be foolish,” I gesture toward the ship’s command chair. “Come copilot with me. It’ll be like lunchtime, just longer.”

Jonathan stares at me, hardware whirring as he weighs his options.

“I cannot assure the upkeep of the observatory without being present there.”

“There will be no observatory to care for! You’ll die if you stay here!” I scream at him.

I’m getting annoyed now. Jonathan should know his duties to me outweigh the observatory’s upkeep. His emotional bonding systems are set to obey me. He’s supposed to care for me.

I sigh and look past Jonathan to the observatory. It’s old, dilapidated, outdated. It will be in the stomach of a celestial being soon. So will Jonathan.

“I can’t let you stay here, Jonathan. Come with me,” I demand.

“It has been a pleasure serving you, sir.” He moves to exit the craft forever.

“Jonathan, no!” I snap. I turn to the control panel and slam the button that locks the doors.

“Sir, please unlock the door.” Jonathan asks.

“No, you’re coming with me,” I say.

Jonathan processes, his eyes glazing over.

“I will unlock it myself.” Jonathan places his hand on the door’s scanner and begins overriding my command. I grab the helm hastily and begin powering up the ship’s engines. Jonathan wouldn’t jump out of a craft already in flight, so that’s what I’m going to do. Fly the ship. Briefly, I consider the others arriving in less than ten minutes, but I decide that they can fend for themselves. They’re scientists, they can figure it out. I start the engines and angle the nose of the Heart of God upward as its speakers count down toward liftoff.

“Departing in three . . . two . . . one . . . liftoff.”

The ship jumps into the air and Jonathan releases the scanner. We gain altitude. I look out of the HOG’s window to see trucks arriving and people getting out, waving their arms in desperation. Others immediately fall to their knees and sob. We exit Earth’s atmosphere and pass the darkening gradient into space.

We settle within view of Earth in case the beast passes by our planet completely. In that case, we will return to the surface and things will be back to normal. I’m hoping that’s what will happen. I set the HOG’s speakers to Earth, sorting through radio news channels and the microphone I have at our observatory. The observatory microphone is just wind. I leave the speaker on the familiar sound in an attempt to calm myself.

I turn to look at Jonathan. He is rigid, hands clasped behind his back. His silicone face is unreadable.

“Jonathan?” I say hesitantly.

His eyes flick to me, and he opens his mouth to speak. I don’t hear what he says.

At that moment, the observatory’s sirens go off over the HOG’s speakers and I turn back to the window. A few moments later the beast comes into view, following the gravitational pull of Earth and I see it move for the first time since I began observing it. The beast pushes the moon aside and spreads its arms wide, then it grips onto Earth and digs its talons into the crust. I see the beast stretch its jaws to the size of continents as it grips onto the planet’s surface with its clawed tendrils. A pitch emanates from its maw and throughout my craft, vibrating the walls and controls and blurring my vision. It’s screaming. The pitch digs into my skull painfully, and I feel the most intense headache I’ve ever experienced throbbing in my brain. Suddenly all sound stops. The beeping monitors, the ship’s humming engines, the screech of the beast.

“Jonathan?” I try to say. I feel the movement but don’t hear the sound. Jonathan’s mouth moves while his body spasms, his radio waves clashing with the frequency, but I don’t hear that either.

“Jonathan!” I scream. My voice is a noiseless vibration that hurts the harder I try. I watch as his body shakes and he moves sporadically, then his head caves in and a small burst of flame erupts from behind his eyes. I feel like a helpless child as I watch his skin melt and the fire spread. I wheel myself over to him and extend my hand to him, but he’s too hot for me to touch. I can’t help him. I watch him burn for a moment. I settle myself next to him and cry.

I turn toward the windows. Through my blurry, tear-filled vision, I get a glimpse of the inside of the beast’s mouth and am reminded of the black hole I had seen over fifty years ago in the observatory. The beast had watched us from the far reaches of space. I saw it years ago and stared into its mouth. Now it is back and I am watching it eat Earth.

It takes a bite of the earth’s surface. Lava spills into space in a flurry of red and orange, landing on the beast and floating out into space. It swallows the piece whole. I watch it devour the earth and drink the magma. Before it finishes, it turns and faces my craft. I stare into its white eyes, motionless. Then I heat the ship’s engines and blast in the direction that the beast had come from.

There’s nothing. The beast ate every star that had been in its way, and now this region of space is solely void.

I look to Jonathan to find that his head is a hole with black ash and wires spilling out of it. He is slumped against the wall of the ship, his limbs in unnatural positions. The beast’s screech killed him. His systems overloaded. He blew up. He’s gone.

I am alone in space. I am in a void of nothing. I’m numb. It’s just me, this ship, and the corpse of a broken android. I stare into the abyss before me.

From the corner of my eye I see a bright light. I use the ship’s monitors to zoom in on it, increasing resolution 100 times. . . 200 times . . . 300 times . . . stop. I see the light in full clarity.

It’s a face.

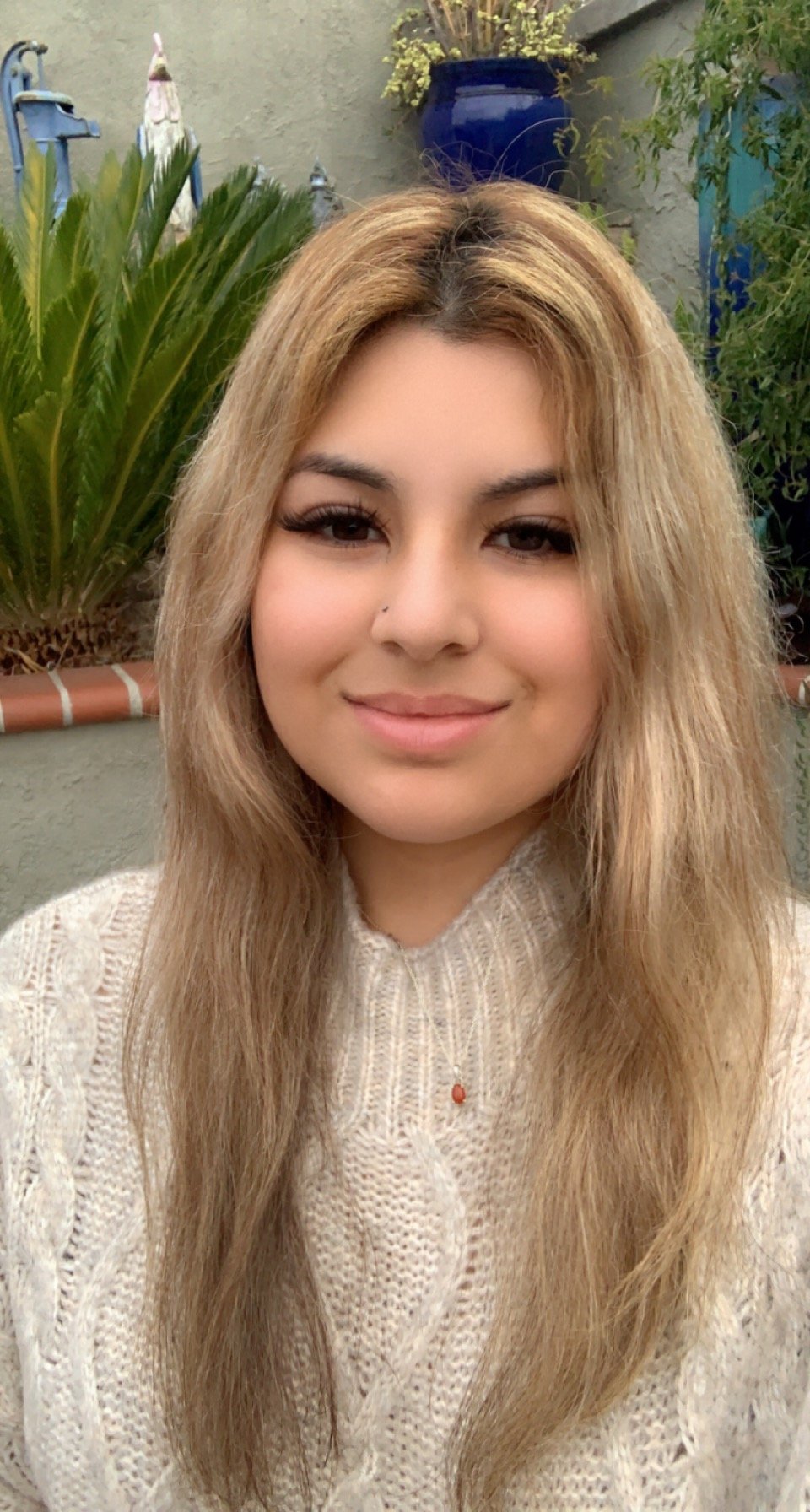

Isabella Elliot

1/14/22

Isabella Elliot is a fourth-year student at UC Davis studying aerospace engineering. Her interests include lost media, controversies, disasters (both natural and unnatural), and deconstruction. When not pursuing her degree in Davis, she lives in southern California with her two dogs.